While we often think of the core and pelvic floor in terms of pregnancy and early postpartum, your core and pelvic floor are so much more. Understanding your core and pelvic floor basics, your tendencies, and how to counter those tendencies can help you reduce symptoms, minimize risk of complications, and have a positive impact on your athletic performance.

What is your core?

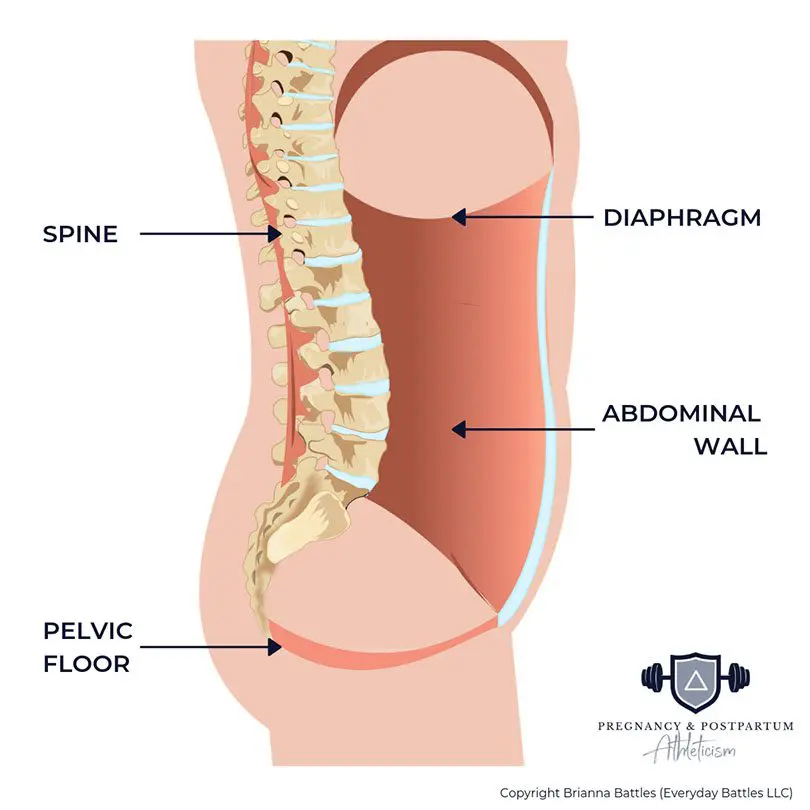

Your core is more than your rectus (or 6 pack abs). Rather, your core is a system of muscles that work together for optimal function. Think of your core as a canister, including:

- Diaphragm – syncing and managing pressure from the top

- Transverse abdominis – deep corset muscles

- Pelvic floor – supporting your pelvic organs (uterus, bladder, and bowel)

When you inhale, your diaphragm naturally contracts allowing your lungs to fill with air. At the same time, your pelvic floor lowers or lengthens, and your belly relaxes.

On exhale, your diaphragm relaxes, pushing the air out of your lungs. In other parts of your core, your transverse abdominis contracts and your pelvic floor contracts and lifts. These are super gentle contractions that you may not even feel happening, but the system is important to be aware of when it comes to counter any tendencies that you may have and decrease symptoms in your athletic endeavors.

It looks like this:

Core, Pelvic Floor, and Athletic Performance

Maintaining an appropriate level of tension in the pelvic floor allows you to have the strength necessary to hold the pelvic organs in place while also allowing the relaxation necessary for urination and bowel movements.

That’s important both inside and outside of the gym.

While it may seem that you want a strong pelvic floor, it’s more important to have a coordinated system, one that’s responsive to the task at hand. Ex: deadlift, sneeze, or run. Too little strength, too much tension, or too much pressure generated in one area can lead to potential issues like incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, or diastasis.

A Coordinated Pelvic Floor

You want awareness, not hyper awareness of your pelvic floor. When you’re hyper aware of your pelvic floor, as often happens after a prolapse diagnosis, with leaking, or during pregnancy, you’re more likely to try to hold everything tight, ending up with excess pelvic floor tension. Your pelvic floor can’t hold that much tension, especially when adding impact or load, likely leading to an increase in symptoms.

Once you have awareness of your system and tendencies, you can translate that into your lifts.

Using Exercise to Help Your Core and Pelvic Floor Symptoms

- Breath holding

Are you someone that holds their breath all the time, bearing down, or sending pressure to the midline? If so, how can we redistribute that pressure using your breath so it’s not concentrating in one spot?

Try breathing into your lats. That’s a cue that works well with athletes to get you to have full ribcage expansion at the start of your exercise which helps to prevent you from collapsing at the top of your core and bearing down into your pelvic floor.

Click here to watch this video.

You can also play around with exhaling either through the whole exercise or through the portion of exertion in a lift. By timing this exhale, you’re allowing your body’s natural system to take place where the pelvic floor slightly lifts on exhale. You’re not looking to have to do this with every rep of every exercise. The goal is to make it automatic so you’re not thinking about it forever.

- Tension

Do you have a tendency to constantly suck in your abs, grip your glutes, or clench your jaw? Tension isn’t isolated. Holding tension in your core, glutes, and jaw means tension in your pelvic floor too.

You’ll want to downtrain and lengthen the system in that case. That may look like reducing tension in your workout by not squeezing your glutes when you squat or at the top of a deadlift, not doing a kegel while you’re jump roping, or relaxing the belly in a run.

- What about coning and diastasis?

Coning along the midline of your belly doesn’t automatically mean diastasis.

A diastasis is a naturally occurring separation of the left and right side of the abdominal wall at the midline, linea alba. The tissue of the linea alba is designed to stretch during pregnancy. Sometimes it just stays a little more stretched out postpartum.

When looking at diastasis, you test for both the width and tension of the linea alba. If you have a slightly wider gap but are able to generate tension in the tissue, that’s not likely an area of concern. Likewise, if you see coning present and the coning is soft to the touch, that may not be as much of a concern.

If the area of coning is more firm to the touch, that may indicate excess pressure being pushed into the midline. Sometimes we can help to manage that pressure with form shifts or breathing pattern changes. Ex: if you have excess pressure into the midline with snatch, pullup, or overhead press, what happens if you bring your ribcage down a bit and not thrust out? The pressure is still there but it’s likely less.

This is also an area that you may need to play around with either more or less core engagement. That doesn’t mean an all out contraction. Instead, look for gentle 2/10 effort.

Your core and pelvic floor play an important functional role within your body. Understanding the core and pelvic floor basics and becoming aware of these tendencies, as well as learning how to manipulate pressure and tension, will help you be able to use this system for positive impacts in your athletic performance.

Want to learn more beyond core and pelvic floor basics? Join us for the FREE Workshop below to learn the strategies you need to prioritize your safety + performance while being mindful of your core + pelvic floor system.

Read More: 3 Tips to Exercise with a Prolapse